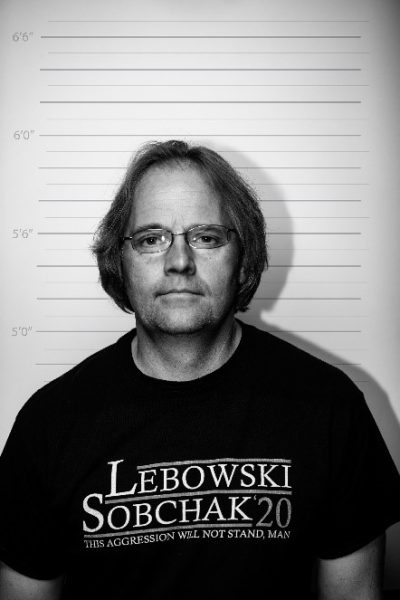

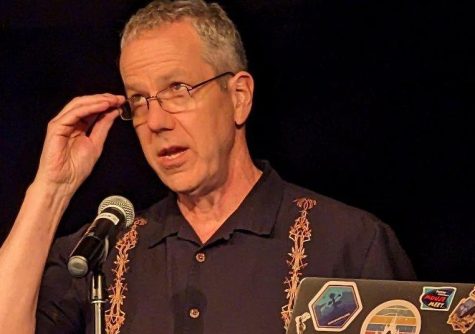

MINI INTERVIEW: Mark Sanders

Interviewed by Libby Dunn – February 2020

How did your latest work In a Good Time come about? Could you talk a little bit about the title?

Various pathways led to In a Good Time. While the final push to publication came quickly (the book was published in September 2019), the book took about four or five years to complete. The poems were finished between 2015 and the Summer of 2019, give or take. Some of the poems began long before that, though. The lyrical narrative, “What is Natural,” for example, started about 2011 and grew to almost 140 pages before I started paring it down. I had a concept in mind, but I started seeing parts of the big vehicle as being better standing on their own in what became the book’s final section. I was always a fan of concept albums, like Jethro Tull’s Thick as a Brick or the Who’s Tommy, but over time I’ve come to realize some parts of a concept stand out and the rest might as well not be there. I may do something with the parts that I cut someday from my long poem, but I may not.

The majority of the poems I started and finished in 2018 and 2019. Some of the pieces were still being tinkered with when I sent the manuscript to WSC Press and Chad Christensen. Between him, JV Brummels and me, we trimmed bunches of pages before we got to the final version. We kicked poems out, kicked them back in, and rearranged sequences. That process took about a month. It was actually a really neat energy that brought the book together in its final form.

The “idea” about doing a book started somewhere around 2015. I went to Nebraska that Fall to do a set of poetry readings, so first conversations may have begun then. I know that I had hinted to JV and Chad that I one day would like to submit a book to WSC Press. They were receptive to it, though at the time, JV and I were discussing the possibility of doing a book of nonfiction, which would have been a departure from the poetry books the press usually publishes. I owned a number of WSC Press books, liked what the press was doing. I have a deep affection for Nebraska and Nebraska letters, and I thought maybe there’d be a good opportunity. Things went to quiet for a few years, and when my book The Weight of the Weather: Regarding the Poetry of Ted Kooser came out in 2018, the conversation started again. This time it was about poetry, though.

The manuscript of nonfiction, by the way, is still being revised; I’ve set it aside quite a number of times these past five years to write poetry instead. I haven’t lost sight of it, but I confess to being slow with it—I want it right. I want it to do things that most books of nonfiction don’t do.

The title of In a Good Time comes from a couple of triggers. At the front of the book, I have an epigraph from Theodore Roethke’s “In a Dark Time”: “I climb out of my fear.” Roethke’s work has long resonated for me, and while so much of his poetry seems very sad, I thought I would climb out of sadness to write “In a Good Time,” a poem that shows up later and is the title piece of my book. I imagine that Modern poet Wallace Stevens’s “In a Bad Time” influenced the Roethke piece. I took a quote from Stevens’s poem to lead into mine. Stevens wrote, “How mad would he have to be to say, ‘He beheld / An order and thereafter he belonged / To it?’” What that line says to me is if we make a negative claim, we’re sentencing ourselves to a mad belonging—or imprisonment. It’s insane, basically, to say our lives are dark or bad when we end up believing in the darkness or badness; we lock ourselves into a self-fulfilling prophecy. In a Good Time is an optimistic look at the world, a world that I had too often over the years related to unhappiness. I decided to climb out of the darkness with this book and to see my world in positivity. At the end of the poem “In a Good Time,” I write, “The world is beautiful because it is the world.” I think that’s a good place to be.

Why do you write? What does poetry mean to you?

I write because it’s what I do, I guess. I’ve always been something of a creative person: I write, I paint, I build. Writing has been a major part of my identity. I started writing when I was still in grade school, and I kept at it. I practiced it like some people practice the piano or dance. Poetry has been my chief interest, though I also write nonfiction, criticism, and fiction. I am probably best at writing poetry; I hope that’s true. But, writing is something I can’t change about myself. I equate it to a kind of DNA. I have green eyes, what used to be brown hair; I am left-handed, and I write poetry whenever I am able. I have a lot of distractions, I confess, but I’ll write something and go back to it weeks and years later. Or, when I have blocks of time, I will spend every moment of those blocks writing. There have been summers when I had a month of my own and I’ve written or started dozens of poems. That makes up for the distracted times.

Poetry has been the most stable part of my life. What it means to me is that I go to poetry when I want something to read. I go to poetry when I want to explore language or the beauty of things described in terms not themselves; I go to poetry when I need a respite from the chaos; I go to poetry because, if we’re endowed with the powers of God’s likeness, poetry puts us very close to the center of creation. “In the beginning was the Word,” and poetry is the word served up best. Poetry has created and recreated me.

What was the inspiration behind your painting featured on the cover of In a Good Time?

I sometimes make attempts at oil paintings, and the cover art for In a Good Time is one of my attempts. I like landscapes, and this makes sense since much of my poetry is lodged in place or locale. My wife and I lived in Idaho for a number of years, and this painting is representational of the high plains around Hell’s Gate Canyon. It’s winter, and I sort of envision the landscape as moving in depths of coldness. In some mythologies, Hell is a place of ice. The horses, though, are there in the midst of all that cold space, grazing, unhurried, comfortable. They’re having a good time, despite all that negative space. There’s a lesson in the visual metaphor, as I hope there’s a lesson in the metaphors of my poems. We can weather the weather.

You are originally from Nebraska, but now live in Texas. How does location impact your writing?

Location makes a great difference, I think. I wonder what kind of writer I might have been had I been born and raised in the city. I can’t really conceive of it because I am not at all fond of cities. I don’t belong there. The truth is, I might not have been a writer at all had I been a city product.

I was raised in a small Nebraska town, and I spent the better part of my life in locations that have modest populations. I like farmland and ranches; I like big horizons. We have a small farm in Texas, and I like that my nearest neighbor is a half-mile or more away. I don’t hear many cars or trucks; I hear owls and coyotes and dogs baying at the darkness. I hear my horses murmuring in the tall grass and not the hurried grumblings of customers walking in a Super Center.

The rural is where I put my poetic feet. I think we need to belong somewhere if we are to understand more fully what it is to be alive. I write about the Great Plains because that’s where I’m from; and, I write about those country locations where I’ve lived, in Idaho and in Texas. Those places gave me life. I have written some decent urban poems, but I seem like a voyeur when I write those. I’m an outsider looking through a window into a room, and it’s not my house. When I write about Nebraska, there’s no window, there’s no house. It’s a pond that I swim.

People talk about the fly-over states, and I have always been troubled with the terminology and the attitude. I’m not in a hurry to get out of the territory. Karl Shapiro wrote a poem many years ago that mocked people who felt that way, who wanted to step on the gas and leave. “The dust settles all questions,” he wrote. I will live out my life in small locales. It’s not such a bad place or way to be.

What makes In a Good Time unique compared to your past works?

In a Good Time is a bright book. It’s optimistic. Life isn’t going to hurt me. It isn’t going to hurt you. There’s an old man persona that shows up periodically in the book, and he’s got a good view of his place in the world. I think angst shows up a lot in my earlier work, but dealing with upset was a process I had to go through to come to In a Good Time. The book is full of redemptions, from “The Messiah Horse,” “The Horse as the Letter L,” “Three Kinds of Pleasure,” “Learning to Walk Again,” and “A Dialogue of Two Spirits,” among others. The bad times of our lives make us champions on behalf of life.

Which writers inspire you and how?

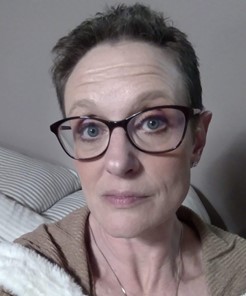

I find myself going back to the same writers. I have a lot of influences from Nebraska: Don Welch, Bill Kloefkorn, Ted Kooser, Greg Kuzma, Karl Shapiro, to name my poetic forebears. I started my Sandhills Press in 1979 and devoted it almost exclusively to publishing Nebraska writers. Nonetheless, I am a sucker for the Romantics, particularly Wordsworth, Coleridge, and Keats, and Yeats when he considered himself a “last” Romantic. I re-read Wallace Stevens, William Carlos Williams, and Theodore Roethke a lot. Of my contemporaries, I like Kim Addonizo’s work, the late Kathleene West, and so many others that I won’t list for fear of omissions. In prose, I like Claire Davis, Mari Sandoz, Willa Cather, Wright Morris, and Cormac McCarthy. Among experimental writers, I like Donald Barthelme and Robert Coover. There’s a really fine prose writer whose work needs to be out among us: Kimberly Verhines. She’s a major inspiration. I’m married to her, by the way, but in all objectivity, she is an amazing writer. I have the rare and private pleasure of reading her essays and stories, and she’s like a razor.

How has your experience as a professor at various institutions impacted your writing?

It’s awfully easy to let a professorship get in the way of writing. When I taught fulltime, I found myself giving away my metaphors, and I spent inordinate amounts of time editing student work when I perhaps should have been editing my own. I’ve been an administrator now for a dozen years, and I confess I like the work a lot; even it, however, has its share of distractions—committee work, politics, assessments, and so on. Anytime something diminishes energy or focus, it probably is harmful to writing. On the other hand, being in higher education has permitted me with an amazing livelihood, and it has financed the habit of writing. I’ve been a good teacher and administrator, and I won’t begrudge what it’s done for me. When I’m at work, I devote myself entirely to the mission of education. I believe I’ve been able to do a lot of good for a lot of people by being a professor. I am certain I have changed lives for the better. I don’t, however, write about the experience. I do what I can to keep my professional and personal households separate.

What was your reaction to your poem “The Still Life” being selected for publication in The New York Times?

The acceptance of “The Still Life” was a happy event. I’m still ecstatic over the news and the inclusion. It all came in a sort of surprising sequence. Naomi Shihab Nye, the current poetry editor for The New York Times, contacted me during Summer 2019 because she was concerned about a mutual poet friend of ours. She sought some information, and I told her what I could. She and I had been acquaintances for any number of years, dating back to the 80s and 90s, and she asked me what I was working on. I had a final draft of In a Good Time, and I told her about it. She asked if she could see the manuscript, so I sent it to her, letting her know that the book would be published by WSC in the Fall. She wrote back to explain she had just become guest editor for The New York Times and that there were a half dozen poems in the book she thought would be good for the publication; she said her initial leanings were for “The Still Life,” and that’s the one she ultimately took. This was August 2019; the poem came out the following December. I told almost no one until it appeared because I was afraid I’d jinx it. Interestingly, “The Still Life” had won the Stephen Meats Prize for Poetry from The Midwest Quarterly during Summer 2019; the poem has been very well received.

This was really important to me, though. I wrote the poem right after my mother died in 2014. While it’s not about my mother specifically, her death brought to mind the idea that those we loved stay with us. There’s a cardinal mentioned in the poem. That was her favorite bird, so that image is hers.

Are you working on anything currently?

I mentioned the book of creative nonfiction, tentatively titled, Homecoming Parade. It’s a collection of about ten lyrical and experimental essays. The title piece was published in Permafrost but went on to receive a notable mention in Best American Essays 2016; that piece is very experimental. It takes place in 1970 at Creighton, Nebraska, not too far down the road from Wayne State; Creighton was my original hometown. Kent State had just happened; the ROTC buildings at the University of Kansas and of Nebraska were taken over by students in protest of Vietnam, and I was 15. The times were transitional and turbulent, and the counterculture was psychedelic. I tried to get the essay to reflect psychedelia. Other essays in the collection appeared in places like Shenandoah, River Teeth, Ninth Letter, among others. Even though most of the pieces have been published previously, I can’t help but revise them. Distance from a piece of work will do that. It’s an important collection for me, and I want it right, even if it means changing something published some time ago.

I have a couple of new poems written since In a Good Time was published, a piece called “Remembering Nixon,” which was recently published in Bosque, and another called “Flannery,” a sort of O’Connor-in-the-hereafter piece. These may be part of a new poetry manuscript, but it’s too early to tell.

I am also working on getting In a Good Time to readers. “The Still Life” publication brought a lot of attention to the book; Betty Flowers, former LBJ Librarian and wife of Senator Bill Bradley, saw the poem in the Times and bought the book. She got some friends of hers to buy it, too. It was cool hearing from her. I also had four poems published in the book nominated for a Pushcart Prize, and five other poems nominated for Spur Awards. The book is submitted to a number of contests, so I hope something good happens. Social media has been a terrific tool to get word out.

What advice would you give aspiring writers?

I’ve written about this a couple of times, once for a piece in The Midwest Quarterly (44.4, 2003) and most recently for a short article for the Stephen F. Austin State alumni magazine. Here’s some of what I wrote for the latter:

First, take time and study, immersing yourself in books and words. The lessons will make all the difference, this handful among them:

Writing is an act within proximity. What we need to write about is here. . . . My favorite writers show us how to claim territory and to write about what we know. Wherever “here” is, is a fine place to begin.

To borrow from Flannery O’Connor, writing is a “habit of being.” Daily hygiene — the brushing of teeth, the combing of hair — is habit, as is driving daily routes to work, or how someone sips a cup of coffee. The habit of being is a writer’s perpetual awareness and requires a degree of selflessness. O’Connor wrote, “You have to cherish the world at the same time that you struggle to endure it.” She also wrote that knowing “oneself is, above all, to know what one lacks . . . . The first product of self-knowledge is humility.” Ego gets in the way of being.

After all, writers are obligated to their readers. Frost called the writer a “kindly gentleman” who writes to succeed for the reader’s sake. Writing is a careful proposition like the art of walking a high wire. Be willing to revise so as not to misstep. William Faulkner wrote, “In writing, you must kill all your darlings.” Stephen King added, years later, “Even when it breaks your egocentric little scribbler’s heart.” While we may love the sound of our own voices or our private imagery, readers need us to connect with them.

Writing should be purposeful. “It is difficult to get the news from poems,” William Carlos Williams wrote, but people perish “every day for lack of what is found there.” Metaphorically, writing brings us the news and weather of our human community.

Good writers read— a lot. As Descartes noted, reading good books is “like a conversation with the finest minds of past centuries.” These conversations teach us much about how to think and communicate. As Ray Bradbury wrote in Fahrenheit 451, “You don’t have to burn books to destroy a culture. Just get people to stop reading them.” Writers help to keep the culture alive.

Mark Sanders is a Nebraska native, born in Creighton and raised on the eastern rim of the Sandhills at Ord. Among his books of poetry, Landscapes, with Horses (2018) was awarded the 2019 Western Heritage “Wrangler” Award from the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. His edited works include A Sandhills Reader: 30 Years of Great Writing from the Great Plains and The Weight of the Weather: Regarding the Poetry of Ted Kooser, both recipients of the Nebraska Book Award, in 2016 and 2018 respectively. In 2007, he was awarded the Mildred Bennett Award for fostering Nebraska’s literary heritage. He has taught at schools and colleges in Nebraska, Missouri, Oklahoma, Idaho, and Texas. He is currently Associate Dean of the College of Liberal and Applied Arts at Stephen F. Austin State University at Nacogdoches, Texas, where he and his wife Kimberly Verhines operate a small farm.

Mark Sanders is a Nebraska native, born in Creighton and raised on the eastern rim of the Sandhills at Ord. Among his books of poetry, Landscapes, with Horses (2018) was awarded the 2019 Western Heritage “Wrangler” Award from the National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum. His edited works include A Sandhills Reader: 30 Years of Great Writing from the Great Plains and The Weight of the Weather: Regarding the Poetry of Ted Kooser, both recipients of the Nebraska Book Award, in 2016 and 2018 respectively. In 2007, he was awarded the Mildred Bennett Award for fostering Nebraska’s literary heritage. He has taught at schools and colleges in Nebraska, Missouri, Oklahoma, Idaho, and Texas. He is currently Associate Dean of the College of Liberal and Applied Arts at Stephen F. Austin State University at Nacogdoches, Texas, where he and his wife Kimberly Verhines operate a small farm.

His latest book is In a Good Time (WSC Press 2019).