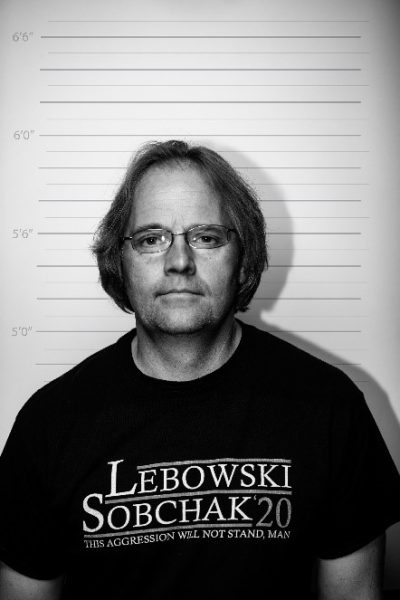

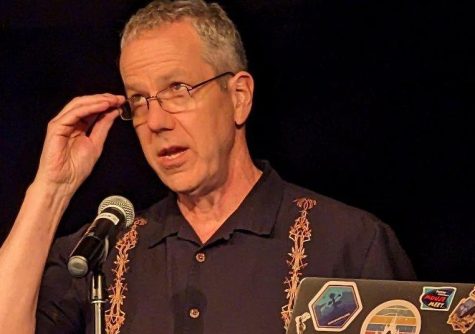

MINI INTERVIEW: David Wyatt

Interviewed by Sean Dunn – April 2019

What inspired you to write Gathering Place?

What notions appear in Gathering Place are those which have shown up in most of my writing. The fact that the book, a first, is published quite late in my writing life has for me made it a kind of selected poems, even though it’s the length of a standard collection. The speaker in the poems often seems bewildered, and that comes out of my personal sense of misplacement, the world, as it drives deeper into a chaos of various ill-advised plans and dreams, seems no place for “right-living,” where give and take, reasonable pursuit, a steady kindness among us all, would go a long way toward lowering a collective blood pressure. But social, cultural, spiritual insanity are everywhere in our neighborhoods, and the need to react to the craziness becomes a calling, though one, in the case of many poets, which has little or no following. The writing process here and elsewhere has been a reasonably long accumulation of experience, and seeing, over time, that no event has lead logically to “the next, the next, the next,” to attempt a quote by the Nebraska-born poet, John McKernan. Therefore, what may be certain in any poem of mine is an implied, “What the hell?”

What does poetry mean to you?

Poetry to me means surprise, a jarring release from expectations, even determinism, the foretold world—”suddenly night cold isn’t so cold,” which is a line by Li Po, who wrote his poems 1,300 years ago. Still in the present.

From what age did you start writing?

I didn’t start writing poems until after I got out of the Army in the late sixties. For some reason, though, I started reading poems in magazines found in post libraries. At the time, many magazines published poems: Atlantic Monthly, Harper’s, Esquire, The New Yorker, Saturday Review of Literature, The Nation; and newspapers, too, such as The Christian Science Monitor. Anyway, I soon discovered that the writing of these poems was nothing like that presented in high school, even college, which I attended before the army experience. Here, the writing was of the moment, which, then, was The Vietnam War, the cultural shift from seemingly complacent middle-class life to distrust of, rage at, the so-called system. Equal rights, feminism, anti-materialism, plus detailed looks at everyday life, instead of further long and overdone discussions of the ancients and their massive “learning.” Also, the influence of non-English speaking poets, from Eastern Europe, Spain and Latin America, and writings by those other ancients, the T’ang dynasty Chinese: Li Po, Du Fu and many others. Black writers in the US were getting much more attention, the bounds of experience ever expanded. Over time, I felt perhaps I could try writing poems, and eventually did. Not much in the beginning but more and more, to the point I couldn’t stop wanting to say something, especially quickly, as in a poem, a poem of the time, which was unsentimental, imagistic, sarcastic, perhaps surprising, as the world became ever more startling in its behavior.

Who are some of your favorite writers? What are you reading now?

Favorite writers of mine have tended to be funny, at least at times. Even writers as elevated as Saul Bellow have pointed out the constant absurdity of experience, through a sharpness, a power of description that can’t be ignored, or argued against by dreamy optimists, believers in, say, personal destiny, a spiritual reward. I’ve gotten comfort, perhaps a strange, even perverse happiness, from reading Donald Barthelme, James Tate, Charles Simic, their getting to the heart of what any person can do in this life to make it, the life, reasonable. For James Tate, “Only a dish of blueberries can pull me out of this lingering funk.”

Has working at a library affected your writing habits or processes?

The job in the library was a marvelous laboratory: a college campus as open as UNO is a good place for focusing on behavior. I worked at the main service desk. I saw certain people regularly, others only once, but whose personalities were performances first to last moment of our encounter. I use quotation a lot, and I was given journals full of sudden insights. Curiosity, asking questions to those who were there to ask me questions; a need for company, even in a work environment, these gave me full-time inspiration.

What’s the significance of the photo on the cover of Gather Place?

The book cover photo was taken by my step-father, a life-long newspaperman. At the time of the photo, he was the editor of a small-town paper near where we lived, in So. California. The house in the picture, a tract house built on land that had recently supported grape vineyards, was my family’s. The man in the corner of the photo, my great-uncle, had moved in with my family after his wife died, just before we occupied this place. I was always drawn to this picture because of its “moody austerity,” which of course I wouldn’t have been able to express at the time; I was ten. And later, part of the appeal was how un-California it looked: no hint of myth-making here, golden light, endless romance. The scene is bleak as any painting of neighborhood life by Charles Burchfield. It fit the irony I saw in any landscape; in this case, the vagueness of possibility in the new but stunted plants along the house-front, the frailty of the TV antenna on the roof, there to capture any number of fictional realities.

You mention flowers in many of the poems in Gathering Place. Where does this affinity of flowers come from?

The question about use of flowers in Gathering Place is interesting because flowers mentioned in poems can be tricky, where they’re connected so completely with romantic love and sentimentality. I guess in my own poems, I’ve attempted to present flowers and other elements of nature, nature both naturally coming forth or constructed, at least partly, through human intervention, as simply an aspect of what presents itself in the landscape of experience. Of course flowers’ often striking beauty, various light, can be offered as a suggestion of wonder and promise, but also as profound contradiction to struggle and seemingly, and persistently, commonplace location: rundown trailer park yard, sudden crocus, bit of soft lavender amid a gray totality, appearing to laugh at these circumstances. Or maybe someone, seeing this specter, holds out for a bluer sky.

Do you have any advice or words of wisdom for aspiring writers?

Advice and words of wisdom. I don’t have much or many, except to say a person, through persistence in writing, eventually believes that he or she must continue doing it, whatever, if any, the reward or lack of attention by others to what she or he has produced. I can’t really determine motivation. In my own case, early and middle on, I couldn’t stop believing in my discoveries, which never were about coming up with whole or (not in this life) perfect poems. I was attracted to my being susceptible to the formulation of image and simile, in the sense that, figuratively, it was possible to restructure the external world, on paper. The newness I thought I was expressing, in very small amounts, did provide an energy I tried using in daily life, as perhaps a way of stalling tedium and postponing disappointment.

DAVID WYATT was born in Southern California a year before the end of World War II, spending his childhood and early twenties in the Golden State, an agricultural and horticultural paradise well into the Fifties. Before and after time in the US Army in the mid-Sixties, Wyatt attended San Diego State, the University of Nebraska, Omaha, and the University of Oregon, where he held a graduate teaching fellowship in creative writing. He has also lived in Illinois, Long Island and Seattle, working (and not working) various jobs. He has been employed at UNO’s Criss Library since 1996. Wyatt was awarded a Distinguished Merit Fellowship from the Nebraska Arts Council in 2006, and won the inaugural Loraine Williams Poetry Prize from The Georgia Review in 2013. He has published poems in ABZ, The Christian Science Monitor, Prairie Schooner, Natural Bridge, The Georgia Review and Poetry. He lives in Omaha with his wife, Susan. Gathering Place is his first full-length collection of poetry.

DAVID WYATT was born in Southern California a year before the end of World War II, spending his childhood and early twenties in the Golden State, an agricultural and horticultural paradise well into the Fifties. Before and after time in the US Army in the mid-Sixties, Wyatt attended San Diego State, the University of Nebraska, Omaha, and the University of Oregon, where he held a graduate teaching fellowship in creative writing. He has also lived in Illinois, Long Island and Seattle, working (and not working) various jobs. He has been employed at UNO’s Criss Library since 1996. Wyatt was awarded a Distinguished Merit Fellowship from the Nebraska Arts Council in 2006, and won the inaugural Loraine Williams Poetry Prize from The Georgia Review in 2013. He has published poems in ABZ, The Christian Science Monitor, Prairie Schooner, Natural Bridge, The Georgia Review and Poetry. He lives in Omaha with his wife, Susan. Gathering Place is his first full-length collection of poetry.